by Michael Edwards, Professor of Electronic Composition

What is electronic composition?

First of all it’s a course of study which is part of the Integrative Composition portfolio at ICEM: a four-year Bachelors or two-year Masters course.

More generally, perhaps the more relevant question at this juncture is: what isn’t electronic composition? OK, that’s a little facetious but technologies developed out of and for electronic composition are found in many genres of music practised today, even in those where the casual listener wouldn’t immediately think of electronic composition. For example, the use of sequencers and Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) in the production of pop and film music; DJ software and hardware in dance clubs; virtual orchestras achieved through advanced sampling techniques; physical modelling and other synthesis techniques in keyboard performances of various genres; music notation software and score emulation in instrumental composition; and algorithmic composition techniques, with or without Artificial Intelligence or Machine Learning, for jingles and elsewhere.

OK, but what is it really?

Traditionally viewed, electronic composition focuses on the creation of sound itself via electronic means, i.e., synthesis/sampling/processing, both as a compositional act and as the final tonal artefact. Electronic compositions can and should be understood from a historical perspective—in the tradition of Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrete as well as the electronic music of Koenig, Xenakis, Radigue or Stockhausen, or indeed the computer music of the USA from the 1960s onwards—but continues to develop and expand. It includes various new approaches, many of them hybrid, bespoke, and influenced by fields outside of music itself, including but not limited to gaming, computer science, and electronic engineering. The field of live electronics forms a central link between electronic and instrumental composition and is impossible to overlook in the contemporary musical landscape.

(all videos on this page are of compositions by ICEM students)

Many composers today would not necessarily draw a distinction between composition (i.e. instrumental) and electronic composition, simply because many or even most of their works are hybrids. This is great. All the same, while a lot of composers might be using electronic composition techniques to some extent, many are unaware of even the basics under the hood of their various technologies. There’s an awful lot to learn and gain from here. Rather than being merely an add-on, the technologies we use really should be making an impact on the structural and aesthetic dimensions of a work’s development—just as detailed knowledge of notation and specific musical instruments‘ attributes shaped the music made with those technologies in both the past and present.

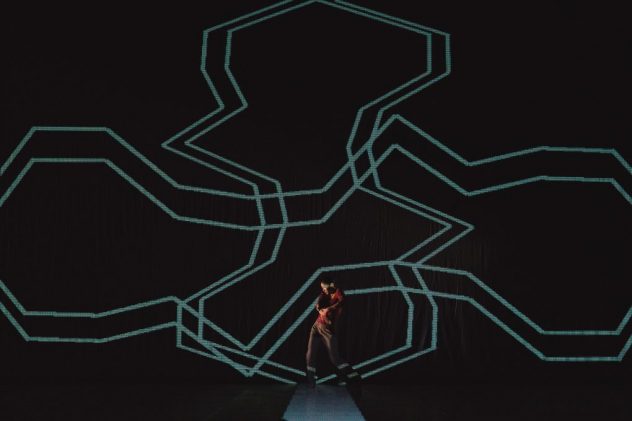

As a consequence of this, students at the Folkwang learn in detail about sound synthesis, studio techniques (both analogue and digital), algorithmic composition, digital signal processing, and different aspects of computer programming as they affect and involve those domains. Musical projects include fixed-media works created with DAWs but also sound installations or works for instruments and electronics using real-time programming environments such as MaxMSP. Essentially, students are encouraged to try out as much as possible in this vast and fascinating area—initially as demanded by the various courses on offer but also and increasingly according to their interests—then turn their newly-honed skills towards developing hybrid software/hardware environments for the realisation of their own particular musical goals. Only thus will the field continue to expand.

Great, so what isn’t it then, after all?

In terms of Electronic Composition at the Folkwang, this is generally not instrumental music played on electronic synthesisers, instrumental music mocked up in a sequencer/DAW, or commercial pop and electronic dance music which explicitly relies on electronic/digital technologies but is essentially instrumentally conceived.

However, aspects of these various endeavours can certainly be supported and developed in the context of an electronic composition course. Ultimately composers are of course not limited to a single technological or aesthetic approach, rather, they are encouraged to expand and intermingle aesthetics and technologies through a multifaceted study of various techniques, some established, some emerging, others developed directly by students and staff themselves to achieve bespoke environments. Electronic Composers are flexible; they have a multitude of skills ranging from composition to performance to software development to audio engineering to hardware hacking.

What kind of students are you looking for?

Aesthetically speaking, my colleagues and I are open to all kinds of applicants, including those with more of a pop or electronic dance music background. These will include people already practising or seriously interested in becoming digital/electronic composers, but also creative laptop performers; obsessively meticulous digital sound producers; glitch-happy hardware hackers; sound designers itching to go further and delve into the development of musical structure; interactive sound installation artists; performer-composer-improvisor hybrids wishing to focus on the world of electronic and computer music; classically-trained composers wanting to break into the digital age…

Of course we’re looking primarily for applicants who want to establish themselves as composers, i.e. as artists. This will usually mean a career as a freelancer, though academic and other careers can arise out of our degrees, such as sound engineer, multimedia developer, film/TV composer, web content provider, computer programmer, etc. Composition in general is a highly competitive area and we believe that the diverse and intense course of study we offer will provide our students with the necessary artistic and technological expertise to succeed and meet the various demands of the field.

Whether you apply for a Bachelors or Masters we’re looking for people with demonstrable talent and experience with (electronic) composition and a desire to learn a wide range of skills in the field. Technical aspects cannot be avoided in these courses but technique is always framed as serving the artistic and aesthetic goals, rather than as an end in itself. Especially in the one-on-one lessons, there is a lot of scope to focus upon what interests each individual student, but students are expected to be open to new ideas and approaches to making music. Why? Because you never know what kind of artistic success can arise out of doing something creative which you’ve never even considered before.

And what’s so special about Electronic Composition at the Folkwang?

The depth. I know few if any other courses that offer the same depth of study in so many aspects of the discipline yet at the same time offer contact points to other disciplines to further the students‘ outlooks and experiences.

The Folkwang has famous dance and physical theatre departments; it has a fantastic design school with staff not just interested in music and technology but active as musicians themselves; it has the opportunity to study Composition and Visualisation with all the concomitant connections to the world of film and video art—this is something our students particularly benefit from; plus the extensive collaboration with instrumental students specialising in new music allows for the regular performance of compositions with and without electronics at a level and with a frequency that I, as a university teacher with thirty years experience, have never experienced elsewhere.

On top of this, the small student numbers mean that the individual attention each student receives is very high in comparison to the vast majority of educational establishments I know of and have worked in, internationally. There aren’t many places left where Bachelors students receive a full hour of one-on-one composition tuition every week, and this for thirty weeks a year.

Then there’s the technical support. One of the things that amazed me when I first started teaching at the Folkwang is the level of technical and infrastructure assistance our students receive when realising their works in concerts, recordings, installations, etc. I regularly attend hour-long concerts of works by one student supported by five or more members of staff on mixing desks, lighting rigs, and stage management. Most students around the world will not be used to anything like this kind of artistic environment. I sometimes worry that we’re actually spoiling our students, because the real world isn’t like this very often either.

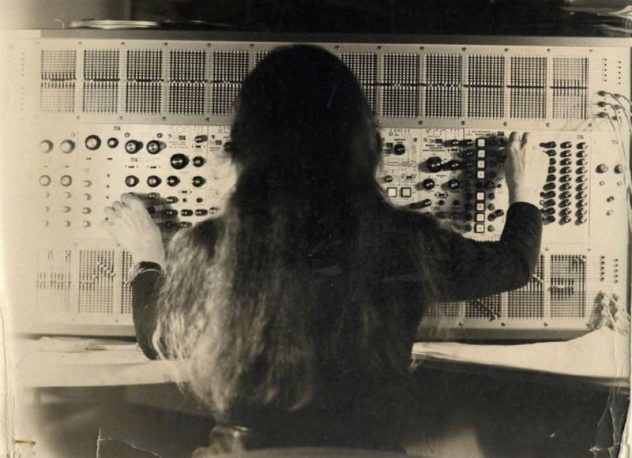

Add to all that a fantastic recording studio, staffed full-time by excellent recording engineers; amazing bespoke quad and octophonic loudspeaker installations in concert halls; an enormous and unique analogue synthesiser housed in a specially-built analogue studio; and a 20.1-channel Audio System with an Astro Spatial Audio 3D Audio Rendering Engine in our main teaching studio. Take a look at our studio gear page for more details.

One more thing that I don’t think international students are always aware of: Germany still offers many courses of study free of tuition fees to all accepted students no matter where they come from. This is truly amazing in this day and age. (There is however a small contribution required, currently 321 Euros per semester, for the student union but also to receive the semester ticket allowing you to travel without further cost on all transport within North Rhein Westphalia—e.g. to Cologne, Düsseldorf, Bonn, etc. See the enrolment web page for more details.)

What’s the down side?

None. Well, OK, some people have preconceived notions of Essen, in the Ruhrgebiet, the old industrial heart of Germany, sitting in coal smoke and dust. In fact ICEM is in Essen Werden, a small town 10km to the south of the city. It’s very pretty here. Essen itself was Green Capital of Europe in 2017, a testament to the regeneration that has taken place over the decades since heavy industry dominated the landscape.

There is one issue I can think of that might affect but hopefully not deter international students: most classes are taught in German. Of course, depending on the professor, one-on-one teaching may be offered in English or other languages, and you do not need to have German language skills at the time of application, rather, by the time you start studying. The level required for Integrative Composition is B1, as offered by the Goethe Institute. See the international applicants web page for more details.

Summary of main points

- electronic composition techniques are

- found in many genres of music practised today

- multi- and interdisciplinary

- constantly expanding

- a core part of contemporary composition

- electronic composition @ICEM is generally not just

- instrumental music played on synthesisers

- pop or film/tv music instrumentally conceived but made on computers with standard, commercial software

- limited to MIDI sequencers

- electronic composition @ICEM is available as

- part of the Integrative Composition portfolio

- a four-course Bachelors course

- a two-year Masters course

- students learn

- composition in general but specifically the techniques and aesthetic concerns of music involving electronics

- a multitude of wide-ranging skills applicable in a similarly wide range of careers

- digital sound synthesis

- analogue sound synthesis

- studio techniques (both analogue and digital)

- algorithmic composition

- digital signal processing

- computer programming

- students have

- one-on-one lessons with their professor every week, 30 weeks of the year

- access to excellent, well-maintained studios and performance venues

- breadth and depth: small-group, in-depth classes covering a broad range of topics and aesthetic approaches

- close contact to other artistic disciplines including dance, physical theatre, design, instrumental performance, etc.

- ample opportunity to have their works performed both within the Folkwang and in collaboration with partner institutions such as the NOW! Festival, Park Sounds, Extraschicht, etc.

- no tuition fees

- projects include

- fixed-media works created with digital audio workstations

- live electronics

- multi-channel audio

- works for instruments and computer

- sound installations using real-time programming environments

- hybrid software/hardware environments